Since the economic crisis labour productivity growth in the UK has been very poor. The Bank of England estimate that output per hour (productivity) is 16% lower than it should be given pre recession trends. With output recovering and high levels of employment, many argue that the so-called ‘productivity puzzle’ is the reason behind lagging wage growth.

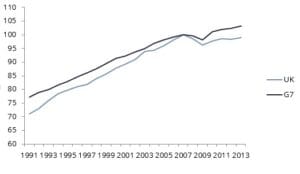

The TUC recently published a report arguing that Tory austerity is to blame for the low productivity, suggesting that the government need to invest to increase wage growth. Whilst austerity is unlikely to have been beneficial to productivity growth, this does not explain the longer term productivity gap. Productivity in the UK has been consistently below the G7 countries since 1991 (see graph).

Source: ONS

So if not austerity, why are we less productive than many of our neighbours?

Macroeconomic theory gives us a number of ideas as why this might be. One of which is known as the endogenous growth theory. Put simply, this is the idea that growth is driven by innovation, knowledge and investment in infrastructure. The LSE Centre for Economics pre-election briefing also argues along similar lines, suggesting that the productivity gap is (at least partly) driven by low investment in innovation and infrastructure.

More spending on infrastructure projects in the UK is vital, to stop reliance on creaking century-old Victorian infrastructure, bridge the well-documented North-South divide and give the South-East the additional runway it needs.

Correct and efficient infrastructure investment is currently the job of Government. But Labour plan to create a National Infrastructure Commission – an independent body which will focus on infrastructure decisions. This is good news as long as it switches the focus to long-term decisions. Investment in schools, transport and housing will benefit many generations, so giving the decision making powers to a body focused on the long-term is likely to be hugely beneficial.

The examples of HS2 and the indecision regarding where is best to deliver runway capacity (amongst many other non-transport examples) highlight the need for these decisions to be made independently of short-sighted governments.

Filling the productivity gap is the task for future governments. Whilst low innovation and an ageing population are making this harder, correct and long-term investment decisions will surely help.

Consultant, Volterra Partners

Top Image: “productivity” by Sean MacEntee under license CC BY 2.0