The second in our series of blogs looking at how Paul Buchanan has continued to develop the techniques and spread the application of WEBs.

Can WEBs be negative?

I spent many years after Crossrail espousing the power of WEBs: the economic growth that resulted, the additional tax revenues accruing to government and all of the good things that follow high density, rail-enabled employment creation. It was more than a decade later when I discovered ‘anti-WEBs’ or how transport infrastructure investments can create negative WEBs.

That discovery was made in Toronto, whilst advising them on rail and WEBs. It is always good to understand the history of a place before making forecasts of its’ future so we spent some time examining development planning and economic growth as far back as we could. It is a sad story. Toronto from the 1950s to 1980s was a public transport city with a thriving metro and development focused within the city centre. Implementation of multiple orbital and radial motorways in the 1980s and 1990s, combined with competitive tax policies from suburban authorities, changed that pattern drastically and by the early 2000s employment growth was almost entirely focused around the orbital and radial motorways, well outside the city centre.

The result was (predictably) an explosion of car traffic and congestion on the main roads. Those commercial developments which seemed so accessible when the highways were running at free-flow speeds suddenly don’t look such a good investment when the roads are highly congested.

Therein lies a key policy dilemma for city authorities and transport economists: the interaction between transport and land use. There are two key issues:

- Rail infrastructure leads to dense development and strong radial demand patterns which railways are ideally suited to serving.

- Road infrastructure leads to dispersed development and complex demand patterns which are very difficult for any transport mode to cope with. Rail can’t provide the frequency and variety of routes, roads can’t cope with the high demand.

The distinction between road and rail becomes even clearer when you consider the costs of serving travel demand. On highways the higher the demand the slower the speed and the higher the generalised cost of travel as congestion reduces speed. On rail it works the other way round, the higher the demand the higher the frequency of service and the lower the generalised cost of travel. The impact of the land use response on transport is negative for roads and positive for rail.

Our advice to Toronto was to invest in rail, align policies to maximise the land use response in the city centre and change the distribution of future growth back towards the city centre. There are strong financial, economic and environmental reasons for that strategy.

1980 – most jobs still clustered in the city centre

1999 – almost no growth in the centre but a large increase in jobs clustered around the new freeways

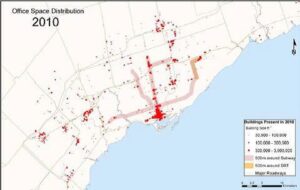

2010 – significant employment clusters well outside the city centre. Demand growth reduces accessibility provided by the freeways

Image: Toronto in 2010 by Guilhem Vellut is licensed under CC by 2.0