Partly due to its success in attracting jobs and talent, demand for housing in London has outstripped supply and now home ownership is unaffordable for many households. In a well-functioning market, increases in house prices should incentivise large scale housing development. But this simply has not happened. So what is constraining housing development in the capital? Or, in the jargon of economics, what are the barriers to entry?

A 2016 study by Christian Hilber and Wouter Vermeulen at the London School of Economics (also the subject of an interesting recent talk) provides us with some answers.

Hilber and Vermeulen assessed the impact of three different supply constraints on house prices across England: those imposed by the planning system, a lack of physical space and hilliness.

Employing rigorous statistical methods, they find that the planning system in England is the main cause of the high prices. In the absence of these regulatory constraints, the authors estimate that house prices in England would have increased by about 100% less (after accounting for inflation) between 1974 and 2008. A lack of physical space for development is also an important factor in urban places such as London.

Hilber argues there are three key flaws with the current system.

The first is that the system is too complex. That complexity makes it costly to develop and involves lengthy consultation process that give significant weight to NIMBYs.

Second is a lack of local fiscal incentives. Permitting new development is costly for local authorities as they incur additional infrastructure and service costs but our centralised tax system means that they do not receive sufficient tax revenues to offset these costs.

This issue is likely to worsen in the short term with proposals for local business rate retention. Business rates are a commercial tax; without similar proposals to devolve property taxes, local authority’s incentives will be skewed in favour of permitting offices and shops. Commercial growth is vital to maintaining London’s competiveness but not if they are at the expense of housing delivery.

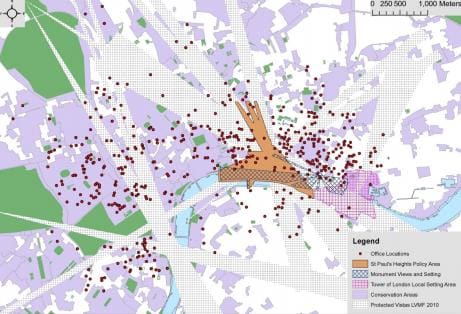

The final flaw is that the current system prevents residential development in all directions. In London the green belt stops development from spreading out horizontally and height restrictions and view corridors prevent vertical development. The map below shows just how much of central London is restricted for development due to conservation areas and protected views.

The capital is a victim of its own success but the British planning and tax systems are largely responsible for its housing crisis. Sadly it seems as though the recent housing white paper shows that the government is no closer to solving this issue.

Map: Taken from SERC DISCUSSION PAPER 154 by Professor Paul Cheshire